THE REALITY

People are living longer into old age. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of people in England aged 65 and over rose by 23%, and the number of people aged 85 and over rose by 28%, compared with 8% for all age groups. The number of people in England aged 65 and over is projected to increase by a further 19% over the 10 years between 2016 and 2026, and by 45% over the 20 years between 2016 and 2036. For people aged 85 and over, there is projected to be a 24% increase between 2016 and 2026 and a 90% increase between 2016 and 2036. Younger adults with learning or physical disabilities are living longer, with increasingly complex conditions.

COSTS WORLDWIDE

The cost to the NHS of “delayed discharges” has spiralled to £820 million per year, according to a new report from the National Audit Office.

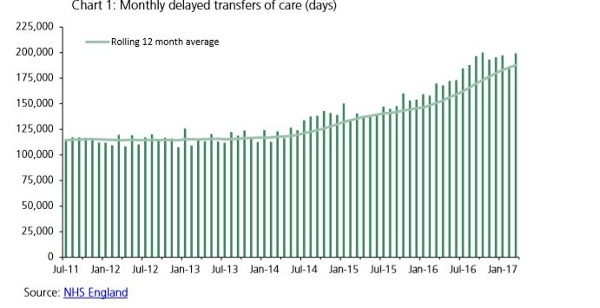

Between 2013 and 2015, official delayed transfers of care rose 31% and in 2015 accounted for 1.15 million bed days – 85% of patients occupying these beds were aged over 65. The NAO estimates that the real number of delays is around 2.7 times higher than those officially counted. In 2016/17 there were 2.3 million total delayed days in England with 1.3 million of these attributable to the NHS, averaging around 6,200 delayed transfers of care per day with around 3,600 of these attributable to the NHS.

The problem of delayed transfers in not confined to the UK and is recognized in countries such as Sweden, Norway, New Zealand and the USA.

Studies in the United States (US) showed that increased re-admissions may reflect the following: sub-optimal assessment of readiness for discharge, fragmented discharge planning, a breakdown in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and community physicians, inadequate post-discharge care and follow-up, or some combination of these processes. In the US, discharge planning is a legally mandated function for hospitals. It is also one of the “basic” hospital functions as outlined in Medicare’s Conditions of Participation from Centres for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

CAUSES

Workforce capacity issues in health and social care organisations are making it difficult to discharge older patients from hospital effectively. Making sure older patients stay in hospital no longer than necessary is a complex issue that requires a coordinated response across health and social care organisations. Lack of specialist complex seating equipment can also impact the patients being discharged. The DOH found a number of joint working across national health and local government organisations however it was complex and so they coordinated activities formally in December 2015 when it established the Discharge Programme, which aimed to show a vision of “what a good patient flow and discharge looks like”. In the USA they have carried out further environmental studies that raise issues like education and post discharge advise and failure with adequate community provision.

FINANCIAL AND HUMAN COSTS

Minimising delayed discharges is supposed to be a top priority for hospitals. NHS guidance states that elderly patients should be moved out of hospitals as quickly as possible once they are deemed to be medically ready for discharge. Delayed discharges are associated with mortality, infections, depression, reduction in patients’ mobility and their daily activities. Studies highlight the pressure to reduce discharge delays on staff stress and inter-professional relationships, with implications for patient care and well-being. Keeping patients in hospital longer than required can have a number of detrimental effects. Long stays can affect patient morale, mobility, and increase the risk of hospital-acquired infections. Effects on mobility can be particularly felt by older patients. As Professor John Young noted in the 2014 National Audit of Intermediary Care: A wait of more than two days negates the additional benefit of intermediate care, and seven days is associated with a 10% decline in muscle strength, hardly an advantage for people with frailty for whom muscle weakness is a defining characteristic. Most of all delays impose a huge human cost on real people with real families and real concerns marooned in hospital.

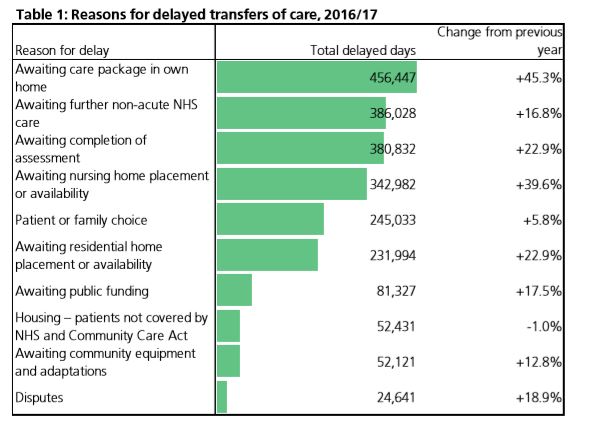

NHS England’s delayed transfers of care figures for the past year (above table) show a marked rise in delays due to ‘awaiting a care package in own home’, up 45.3% in comparison with the previous year. There have also been increases of over 10% for ‘awaiting completion of assessment’, ‘awaiting nursing home placement or availability’, ‘awaiting residential home placement or availability’, ‘awaiting public funding’, and ‘awaiting community equipment and adaptations’.

One of the 20 recommendations from the Department of Health – discharging older patients from hospital suggests, that the NHS England and the NHS Improvement should seek to understand which contracting and payment mechanisms offer the best incentives for community health providers to assist with increasing activity when required.

SOLUTIONS

Seating Matters can help with easing the burden of the delayed discharge process. Their seating equipment has been extensively researched with the Ulster University and has shown the positive contributions their seating devices can have on the care of the elderly in hospital, rehabilitation and nursing home environment. Currently Seating Matters are partnering with hospitals in Southern Ireland and England to quality improve the discharge process and make a very complex seating discharge system flow better which will ultimately lead to addressing delayed discharges by reducing length of stays, improve financial outcomes and ultimately enhance the quality of life to those who are at risk of mortality due to poor seating and delayed transfer of care. All delays impose a huge human cost on real people with real families and real concerns marooned in hospital, nursing home environments or rehabilitation facilities.

How easily we can lose sight of this?

Contact us to day for more information. We can work in partnership with health and social care settings to improve health and well being for patients.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD YOUR RESEARCH SUMMARY

References:

1.Bauer M; Fitzgerald L; Haesler E and Manfrin M (2009) Hospital discharge planning for frail older people and their family. Are we delivering best practice? A review of the evidence. Journal of Clinical Nursing 18 (18) 2539-2546

2.Carroll A and Dowling M (2007) Discharge Planning: communication, education and patient participation. British Journal of Nursing 16 (14) pp 882-6 Department of Health. (2010) Ready to go? Planning the discharge and the safe transfer of patients from hospital and intermediate care. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http:/www. dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_113950 (accessed 10th July 2018)

3.Healthwatch England (2015) Safely Home: What Happens when People Leave Hospitals and Care Settings? http://www.healthwatch.co.uk/sites/healthwatch.co.uk/files/170715_healthwatch_special_inquiry_2015_1. pdf (accessed 10 July 2018)

4.Hockey L (1979) A study of District Nursing – the development and progression of a long-term research programme. PhD. The City University

5.Knight D, Thompson D, Mathie E and Dickinson A (2013) Seamless Care? Just a list would have helped! Older people and their carers experiences of support with medication on discharge from hospital. Health Expectations.16 (3) pp 277-291

6.National Health Service England (2014) Safe, compassionate care for frail older people using an integrated care pathway: Practical guidance for commissioners, providers and nursing, medical and allied health professional leaders https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/…/2014/02/safe-comp-care.pdf (accessed 10th July 2018)

7.National Health Service England (2015) Delayed Transfers of Care Data 2015-16. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ statistics/statistical-work-areas/delayed-transfers-of-care/delayed-transfers-of-care-data-2015-16/ (accessed 10 July 2018)

8.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) Transition between inpatient hospital settings and community or care home settings for adults with social care needs https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG27 (accessed 10th July 2018)

9.Nursing Times (2015) Older patients in Sussex given food packs when discharged 28th September online http://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/older-people-nurses/older-patients-in-sussex-given-food-packs-whendischarged/5090695.fullarticle (accessed 17th July 2018)

10.Oliver D, Foot C and Humphries R (2014) Making our health and care systems fit for an ageing population. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/making-health-care-systems-fit-ageingpopulation-oliver-foot-humphries-mar14.pdf (accessed 10th July 2018)

11.Morse A, Discharging older patients from hospital, 2016 National Audit Office. Department of Health.

** This post was originally published on http://blog.seatingmatters.com/delayed-discharge-in-hospitals